George Floyd: Race and Protest in Ireland

Protestors outside the US Embassy in Dublin

There have been protests in cities across Europe this week in solidarity with those in the US sparked by the death of George Floyd. The marches in London, Berlin and Amsterdam might have been anticipated; the location of one of the largest protests in Dublin, Ireland may be more surprising.

Estimates of the crowd size at the march in Dublin on Monday put it at “over 5,000”, a remarkable turnout in the midst of a pandemic and with social distancing rules still in place in the country.

What did the protest - its occurrence and its scale – signify? The messages, in Ireland as elsewhere, are mixed, reflecting both global and local issues.

The World is Watching

The Dublin event was global in its mediations and messaging, an example of the growing symbiosis of social media and transnational protest movements to propel civic activism. A driving force is Black Lives Matters, the American social movement that has become a globalised phenomenon with influential circuits in youth and popular cultures as well as protest movements around the world.

The Dublin protest was predominantly made up of young people and strongly promoted by popular social media and music performers. The rally replayed iconic text and imagery via social media and placards, banners, and chants – “Black Lives Matter”, “I Can’t Breathe”, “No Justice, No Peace”, and “Silence is Betrayal”. Body language was also symbolic - a bent knee and a clenched fist as shorthand references to American protest iconography.

This is all of a piece with many protests across Europe, and it is clear that the demonstrations are posed against the Trump administration, especially an abandonment of global leadership which was already evident with the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a deep European disillusionment with the US today that swells the passions and numbers in the protests.

The British journalist Ben Judah has suggested the European marches signify a “new transatlanticism”:

Ironically, just as the old ideological West, of the G-7, transatlantic intellectuals and NATO-focused think tanks is breaking down a new kind of transatlantic experience, born out of a common virtual Instagram and TikTok world, is coming alive.

However, there is much in this new form of transatlantic protest that is familiar from earlier versions. It is striking how much of the signage at demonstrations in different countries is in English, clearly intended as messaging to the US. In Dublin as elsewhere there were signs reading “The World is Watching” - echoes of “anti-American” demonstrations in many cities during the Vietnam War and again following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. At such times the world holds a mirror up to America, denouncing its hypocrisies, measured in the distance between its soft power rhetoric and its hard power actions.

There is some irony in campaigners in grassroots protests across Europe, against injustices in the US, taking their cue from American activists, mimicking their methods and discourse. Not for the first time, European disavowals of American power reveal deep affiliations with American culture. Not for the first time, young generations of Europeans feel the need to save America from itself.

Challenging Direct Provision

The demonstrations across the world not only express solidarity with American campaigners but denounce racism in their own countries. In many instances, the denunciations are aimed at violent racist policing. In France, people marched to pay homage to Adama Traore, a French black man who died in police custody in Paris in 2016.

Ireland does not have a large black population and there have not been the spectacular examples of violent racist policing that have been flashpoints in other countries for rallies and for identifications with Black Lives Matter.

In place of such discourses, a local topic in speeches and on placards in Dublin is Direct Provision, the name given to the state’s reception system of accommodating asylum seekers, based in residential institutions across Ireland that are mostly privately owned and run for profit. Ensuring long periods of isolation and limbo for its subjects, the direct provision system has been strongly criticised, both domestically and internationally, as “a severe violation of human rights”.

The symbolic grafting of Black Lives Matters onto protests against Ireland’s treatment of asylum seekers has been questioned by some (including by the Taoiseach Leo Varadker) but it has a logic: it underscores that the migrant crisis is a racial crisis. If we understand racism, following scholar-activist Ruth Gilmore’s definition, as “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death”, we understand how it diminishes the life chances of marginalised people. The direct provision system in Ireland functions precisely as a racist system.

So in Dublin as well as Minneapolis, “I can’t breathe” underlines the vulnerability of lives viewed as disposable, as less than fully human.

Thinking Racially

Across Europe and in the US, there are different, if related, histories of racial experience, racial thinking, and racial ordering of societies. The explosion of protests triggered by George Floyd’s death illuminate the workings of race in fresh ways.

The US has been mired in racial crisis since the founding of the nation. At times this crisis is amorphous, at others it is spectacularly visible, at which times it is often violent but also a focus of protest and agent of change. Barack Obama, commenting on the protests, said “this moment can be a real turning point in our nation’s long journey to live up to our highest ideals”.

Such moments should not be consumed as spectacle, not least because, as Melanye Price writes, “black death has long been treated as a spectacle”. Rather, they should compel us “to think racially”, in Michael Omi and Howard Winant’s words, because “opposing racism requires that we notice race…that we afford it the recognition it deserves and the subtlety it embodies”.

While the protests in Dublin compel such thinking, their spectacular staging can mute notice of more subtle embodiments of racism in Ireland. When an Irish Times reporter spoke to two sisters at the protest who are originally from Nigeria, they explained “silent racism” in Ireland: “It’s not spoken about here because it’s not as serious as what you see in America where people are shot or killed….It hides in the bushes and the trees here; it’s silent.”

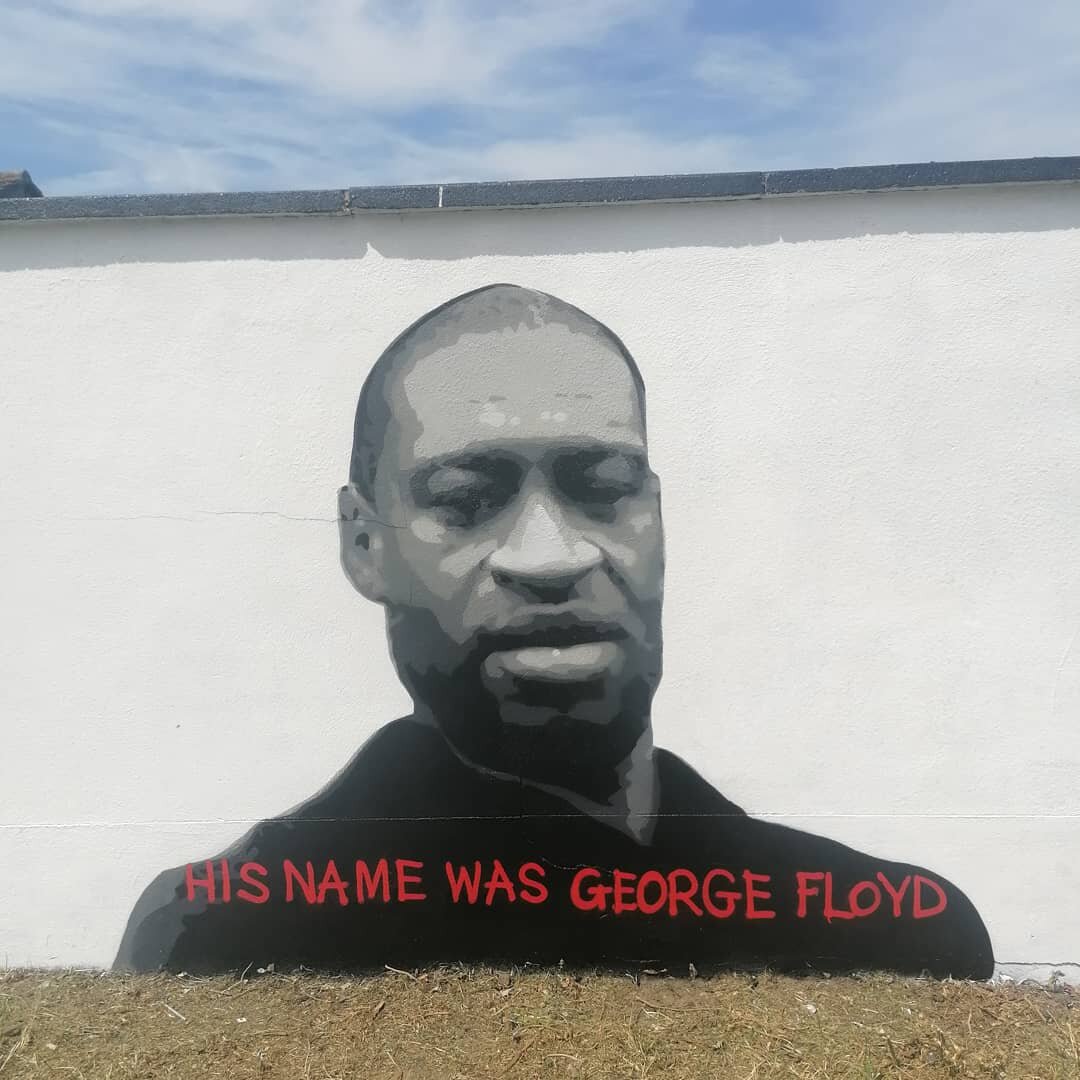

Mural created by Irish artist Emmalene Blake.

Noticing race as a feature of everyday life is an important component of thinking racially. A spur to such thinking is offered by the Irish artist Emmalene Blake, who has created a mural of George Floyd on a wall of a housing estate in Tallaght in South Dublin.

Sharing the finished work on social media, she tweeted: “Teach kids about racism & privilege. Teach them to recognise their privilege - white, class, straight, cis, male privilege and teach them to be allies. Teach them to always stand up to racism and discrimination. Teach them to do better than the generations that came before them.”